Key Points

Urethral obstruction will prevent urination, therefore the bladder becomes very distended

This condition requires immediate medical and frequently surgical treatment

The prognosis is very good after the problem is corrected

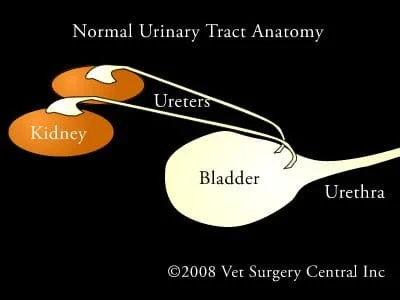

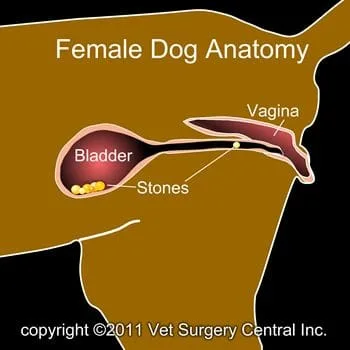

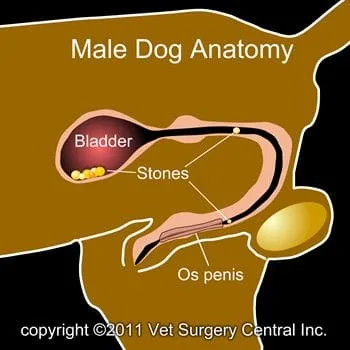

Urine produced by each kidney passes down a tube called the ureter to a reservoir, the bladder. The ureters have a thick muscular wall that propel urine to the kidneys in concerted waves of contraction. When the bladder becomes distended, urine passes out of the body via a tube, the urethra, during urination. In females, the urethra ends in the vagina and in males, the urethra terminates at the tip of the penis. A bone, called the os penis, is located in the penis in male dogs, which narrows the diameter of the urethra. As a result, even small stones can become lodged in the urethra at the level of the os penis. Female dogs do not have a bone surrounding the urethra, therefore small stones can pass through the urethra.

What is an urethral obstruction?

A stone may pass into the urethra from the bladder, thus cause obstruction to urinary flow. The result is that the dog cannot urinate. This problem is most commonly seen in male dogs due to the narrowing of the urethra at the os penis (see illustration below right and endoscopic photo of the urethra at the level of the os penis). Following obstruction to urinary flow, toxins build up in the body as urine cannot be excreted. Within 24 hours of obstruction, the dog will be very ill and can die.

Clinical signs

Warning signs of an urinary obstruction includes straining to urinate with no production of urine, dribbling small amounts of urine when trying to urinate, dripping blood from the penis, abdominal pain, depression and loss of appetite.

Diagnosis

Urethral obstruction is typically obvious on physical examination, as the bladder will be very large and urine cannot be expressed from the bladder. Radiographs (x-rays) are beneficial to determine the location of stones. If the stones are not visible on the radiographs, then a dye study may be needed. Blood work is always performed to see if the patient has a build up of toxins in the blood. Other causes of urethral obstruction may include urethral tumors, urethral granulomas, and urethral structures. Rarely, urethral obstruction is due to a surgical error made during castration (suture encircles the urethra). Below left is an endoscopic (telescopic camera) photo of the inside of the urethra, which shows two stones in the urethra. Below right is a photo of the normal narrowing of the urethra at the os penis.

Treatment

Patients that have a urethral obstruction need immediate treatment. Initial stabilization of the patient may be essential prior to surgery. Affected animals can be dehydrated, have an accumulation of acid in the body, have electrolyte abnormalities and toxin build-up in the body. Fluid therapy is essential to correct dehydration. If the patient is too sick to be anesthetized, then a temporary catheter may be placed through the abdominal wall and into the bladder to relieve the urinary obstruction. Typically within 12 to 24 hours, these patients are well enough to have general anesthesia and stone removal surgery.

Surgery typically involves flushing the stones back into the bladder with a catheter and saline. If this is not possible, then the stone may be retrieved with the assistance of an endoscope (telescopic camera) and specialized instruments. After the stones are in the bladder, they are removed via laparoscopic surgery or if the surgeon chooses, via an abdominal incision. The benefit of utilizing an endoscope to retrieve the stones is that this method greatly reduces the risk of incomplete removal of stones from the bladder or urethra (a number of studies have shown that veterinary surgeons leave stones in the bladder or urethra in about 20% of the cases when an endoscope is not used).

Sometimes stones can get lodged in the urethra at the level of the os penis and these stones cannot be removed. A scrotal urethrostomy is recommended in these cases and stones are also surgically removed from the bladder.

Potential complications

Even though rare, anesthetic death can occur. With the use of modern anesthetic protocols and extensive monitoring devices (blood pressure, EKG, pulse oxymetry, inspiratory and expiratory carbon dioxide levels, and respiration rate), the risk of problems with anesthesia is minimal. Recurrent bladder infections can occur due to infection ascending up the urethra. A urethral tear may occur during the process catheterization of the urethra (see photo below left and video below right showing a urethral tear; this one is small and will heal on its own). Stricture of the urethral tear site can occur if the urethra has been badly damaged or due to necrosis of the urethral wall from the lodged stones.

Straining to urinate may be a recurrent clinical sign and usually is due to a problem with the bladder (inflammation or infection) and not the urethra.

rev 10/2/11