Key Points

By far the most common cause of a tracheal tear is iatrogenic, meaning that the cuff (balloon) at the end of the tube literally pops the trachea.

Cats more commonly develop tracheal tears.

Most of the tracheal tears that are iatrogenic can be treated conservatively, and will seal on their own with no specific treatment.

Surgery is indicated only if the trachea is not healing and continues to leak large amounts of air under the skin and in the chest or if the patient has severe breathing difficulty.

Anatomy

The windpipe or trachea is a tube that passes air from the back of the throat to the smaller airways in the lungs called bronchi. This tube is composed of multiple cartilage, C-shaped rings. The open part of the C-shaped cartilage is covered with a membrane and thin muscle. It is the incomplete rings and membrane roof of the windpipe that gives the trachea lot of flexibility. The trachea anatomically consists of the cervical part that is in the neck and the thoracic part that is within the chest cavity.

What is a tracheal tear?

Most of the tears of the trachea are along the edge of the membrane-cartilage ring junction (along the side of the roof). By far, most of the tracheal tears are due to iatrogenic trauma from an endotracheal tube. This tube is a breathing tube that is passed into the windpipe while the patient is under general anesthesia.

Causes of a tracheal tear from an endotracheal tube include overinflation of the cuff of the endotracheal tube, removing the endotracheal tube from the windpipe before the cuff has been deflated, moving the patient while the endotracheal tube is inflated, and chemical burns of the windpipe from chemical disinfection of the endotracheal tube.

If the endotracheal tube is inflated too much, the blood supply to the windpipe in the area of the cuff is dramatically

Excessive ventilation pressure (i.e. the pop-off valve is left closed during anesthesia) could literally pop the windpipe like a balloon popping.

In spite of taking every precaution possible, sadly, tracheal tears are inevitable in some cases.

Noniatrogenic causes of tracheal tears includes foreign bodies, cancer and parasitic granulomas that weaken the tissue of the windpipe.

Diagnosis

Most tracheal tears are noted following a dental cleaning The common sign of this is the development of air pockets under the skin. The pet owner may note that the skin “crackles” when they stroke their companion over the back and neck. Additional signs may include coughing, difficulty breathing, shallow rapid breathing, anorexia and lethargy. Signs that a veterinarian may also find include dehydration, rapid heart rate, rapid shallow breathing, gagging, coughing, drooling and fever. The diagnosis of a tracheal tear is often based on the history of having a recent general anesthesia with intubation of the airway and the presence of air under the skin. A definitive diagnosis is made by examining the trachea with an endoscope (camera on a tube) or by surgically exploring the trachea for a tear. Take note that even endoscopy of the trachea can miss a tear.

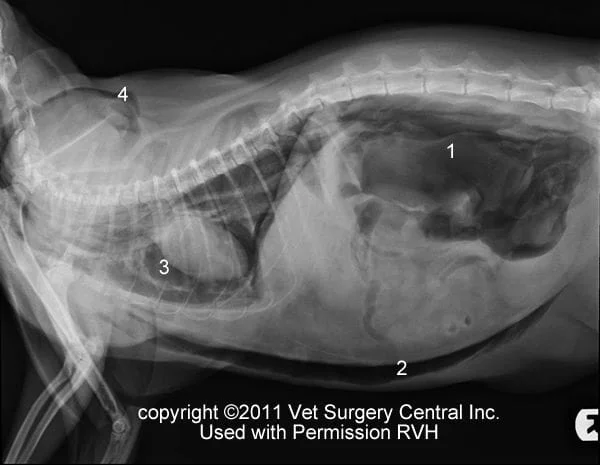

Radiograph below shows: 1. Air in retroperitoneal space (abdomen); 2. Air under skin of the lower abdomen; 3. Air in heart sac; 4. Air under skin over the shoulders

Most tracheal tears can be treated with conservative measures. This includes, confining the patient to a cage, administering pain medication, oxygen support if the patient has difficulty breathing and placement of an active drain system to remove air from beneath the skin. A drain is usually not needed in most cases, as the air will get resorbed with time. If the patient has a tear in the cervical region, a bandage could be applied to the neck; the problem however, is that the location of the tear is generally not known in most cases. If the patient has a tear of the trachea within the chest and air is escaping into the chest cavity, a chest tube may be needed. The indications for surgery include severe breathing difficulty and rapid and progressive accumulation of air under the skin.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients that sustain a tracheal tear is generally excellent. In one study of 20 cats with tracheal tears, 15 were successfully managed with medical treatment alone and 5 needed surgery due to severe breathing difficulty.

References

1. Kästner SB, Grundmann S, Bettschart-Wolfensberger R. Unstable endobronchial intubation in a cat undergoing tracheal laceration repair. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2004 Jul;31(3):227-30.

2. Hudson LC: Respiratory system, in Hamilton WP (ed): Atlas of Feline Anatomy for Veterinarians. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1993, pp 137-141.

3. Dyce KM, Sack WO, Wensing CJG: The respiratory apparatus, in Textbook of Veterinary Anatomy, ed 2. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1996, pp 159-161.

4. Reiss AJ, McKiernan BC: Laryngeal and tracheal disorders, in Wingfield WE, Raffe MR (eds): The Veterinary ICU Book. Jackson Hole, WY, Teton NewMedia, 2002, pp 606-607.

5. Hardie EM, Spodnick GJ, Gilson SD, et al: Tracheal rupture in cats: 16 cases (1983-1998). JAVMA 214:508-512, 1999.

6. Mitchell SL, McCarthy R, Rudloff E, et al: Tracheal rupture associated with intubation in cats: 20 cases (1996-1998). JAVMA 216:1592-1595, 2000.

7. Ko J: Anesthesia tips 1-2-3. Atl Coast Vet Conf Proc:2005.

8. Ko J: Anesthetic mishaps. Atl Coast Vet Conf Proc:2005.

9. King LG: Ventilator-induced complications: Recognition, prevention, and management. Int Vet Emerg Crit Care Symp Proc:2005.

10. Nelson AW: Lower respiratory system, in Slatter D (ed): Textbook of Small Animal Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1993, pp 780-803.

11. White RN, Burton CA: Surgical management of intrathoracic tracheal avulsion in cats: Long-term results in 9 consecutive cases. Vet Surg 29:430-435, 2000.

12. Krahwinkel DJ: Tracheal trauma. Atl Coast Vet Conf Proc:2004.

13. Macintire DK, Drobatz KR, Haskin SC, Saxon WD: Respiratory emergencies, in Troy DB (ed): Manual of Small Animal Emergency and Critical Care Medicine. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005, pp 124-125, 143.

14. Suter PF, Lord P: Trauma to the thorax and airways, in Suter PF (ed): Thoracic Radiography, A Text Atlas of Thoracic Disease in the Dog and Cat. Wettswil, Switzerland, Peter F. Suter, 1984, pp 127-159.

15. Krake AC, Arendt TD, Teachout DJ: Cetacaine-induced methemoglobinemia in domestic cats. JAAHA 21:527-534, 1985.

updated 9/11/11