Key Points

Acute splenic torsion can cause acute collapse with abdominal pain

Chronic splenic torsion can have nonspecific signs of gastrointestinal upset or even port-wine colored urine

Initial stabilization of the patient with early surgical removal of the spleen offers the best prognosis

Anatomy

The spleen is a large blood filter that removes red blood cells that are old, damaged, or are afflicted with parasites and other infectious agents. The spleen is attached to the stomach by a set of ligaments. The spleen has a robust blood supply from its splenic artery and vein, thereby allowing it to be an efficient blood filter.

What is splenic torsion?

Splenic torsion is a condition in which the spleen becomes twisted around its blood vessels. The cause of splenic torsion is unknown, however, is believed to occur after stomach bloat or partial intermittent stomach twisting. Secondary to this, the ligaments of the spleen, which normally hold it in place become stretched. When the stomach partially twists out of position, it pulls the spleen with it. If the spleen remains in this abnormal position, the thin-walled splenic veins collapse and become occluded, yet the artery (which has higher blood pressure than the vein) will continue to pump blood into this organ. The result is a very large, painful spleen.

Signalment

Large, deep-chested breeds of dogs are primarily afflicted, with German Shepherds and Great Danes over represented. This condition occurs in female and male dogs of any age.

Signs

Acute and chronic splenic torsion are the two forms of this condition and have largely different clinical presentations. Warning signs of the acute splenic torsion include abdominal distention, pain, pale gums, rapid heart rate, and weak pulses. Chronic splenic torsion has vague clinical signs of abdominal pain, enlargement of the spleen, intermittent vomiting, diarrhea, weakness, depression , lethargy, anorexia, and in some cases portwine (dark red) urine due to break-down of red blood cells. Both acute and chronic conditions may mimic an illness of the gastrointestinal tract (anorexia, lethargy, vomiting, and diarrhea), thereby making the diagnosis sometimes a difficult one.

Diagnosis

Blood work commonly will show mild to moderate anemia with a decreased hemoglobin concentration. The white blood count is frequently elevated and sometimes the platelet count is below normal. The chemistry profile may show elevations of liver enzymes and increases in the bilirubin (if high enough could result in jaundice). Urine testing may reveal hemoglobin in the urine from the breakdown of red blood cells. A clotting profile may show a reduced ability of the blood to clot.

X-rays of the abdomen will show an enlarged spleen that is displaced out of its normal position. The spleen may be folded into a C-shaped structure. The stomach shape may also be distorted with the outflow of the stomach pulled closer to the inflow tract.luid may be seen around the displaced spleen. Uncommonly gas is seen within the spleen due to an infection of the spleen by anaerobic bacteria (Clostridium).

Abdominal ultrasound will show an enlarged spleen. The veins are distended in the peracute case, but more commonly they are smaller than normal due to the vessels being collapsed from the twisted pedicle and from compression of the distended spleen. A doppler color flow ultrasound study will show reduced flow of blood in the veins and with time the flow of blood in the arteries will also stop.

Although CT scan is usually not needed to diagnose a splenic torsion, this test will show a cork screw soft-tissue mass at the base of the spleen, which is the twisted vessels of the spleen. The spleen is displaced and enlarged and frequently will lack enhancement with contrast (dye that is injected into the patient).

Other conditions that can result in an enlarged spleen include cancer, trauma (hematoma), immune-mediated diseases (hemolytic anemia), abscess, tick-borne diseases such as Ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, and Babesiosis.

Treatment

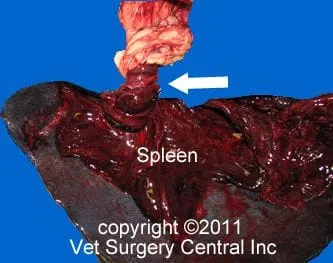

Prior to surgery, initial stabilization of the patient is critical when signs of acute shock are present. This treatment includes the administration of intravenous fluids, blood transfusion, and administration of plasma or hetastarch (vascular volume expander). After the patient is stabilized, surgical removal of the spleen is performed under general anesthesia. At the time of surgery, a large congested spleen (fig below left) with a twisted pedicle (blood supply) is seen (arrow below right). The spleen should always be sent out for biospy to rule out cancer of the spleen. In some cases, a partial removal of the pancreas is essential if it is devitalized. Prophylactic gastropexy should be done at the time of surgery to reduce the risk of stomach bloat in the future.

In the postoperative period, temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and EKG are closely monitored to ensure that your companion is making an uneventful recovery. Blood tests are frequently done in the early recovery period. Intravenous fluid therapy is continued to maintain good hydration. Blood is transfused may be required if the patient is anemic. Some dogs will develop abnormal heart beats that require treatment with medications.

At home, pet owners should monitor their companion for signs of incisional infection, inflammation of the pancreas (anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea), and bloat (abdominal distention, lethargy, and unproductive retching). Exercise should be limited for 3 weeks after surgery. There are no specific dietary requirements following splenectomy; however, your companion’s surgeon may recommend a bland, low fat diet.

Prognosis

Most patients that are promptly treated for splenic torsion have a very favorable prognosis. Literature cited prior to 1990 showed a 74% survival rate, whereas reports after 1990 show a 96% survival rate. The acute form of splenic torsion may have slightly lower survival rate versus those that are chronic.

References

- Fossum TW: Small Animal Surgery. St. Louis, Mosby, 2002, pp 542–544.

- Millis DL, Nemzek J, Riggs C, Walshaw R: Gastric dilatation- volvulus after splenic torsion in two dogs. JAVMA 207(3):314– 315, 1995.

- Montgomery RD, Henderson RA, Horne RD, et al: Primary splenic torsion in dogs: Literature review and report of five cases. Canine Pract 15:17–21, 1990.

- Neath PJ, Brockman DJ, Saunders HM: Retrospective analysis of 19 cases of isolated torsion of the splenic pedicle in dogs. J Small Anim Pract 38:387–392, 1997.

- Slatter D: Textbook of Small Animal Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 2003, pp 1054–1055.

- Stickle RL: Radiographic signs of isolated splenic torsion in dogs: Eight cases (1980–1987). JAVMA 194(1):103–106, 1989.

9/10/11